LURVE ISSUE 11 - MIGRATING

PASSING THROUGH

WORDS BY GIANGI GIORDANO

Throughout time, mankind – either consciously or unconsciously – has given great importance to traveling, intended either as the act of transferring from one place to the other – with the aim of reaching a destination and realising a goal – or as the desire of leaving without neither a destination, nor a goal, but with the purpose of finding one’s inner dimension.

During the Stone Age, our ancestors would perform exceptionally long travels only to find food, and relocate wherever hunting would provide them with more possibilities of survival.

In more recent times, long travels would be carried out because of religion or to conquer new lands. Finally, men started traveling to find jobs and better life conditions than the ones they had, sometimes fleeing from hunger and poverty, which remains a topical subject today.

In the present days and within our opulent Western society, travel tends to take on new connotations – potentially questionable ones – such as mass tourism. Today we travel with staggering hurry, with a gluttony uninterested in the contents of what we see, deaf to the circumstances which we experience, blind in front of the differences we discover.

But traveling remains a chance for us to give a deep twist to our daily existence. It isn’t a coincidence – for example – that the theme of traveling has been largely exploited by the movie industry, a keen observer of the ways in which we live and think.

From the exotic views of the Lumière brothers to road movies that have characterised its history – beginning from John Ford’s masterpiece, “Stagecoach” – travelling has occupied an important place in the history of the seventh art, both in its real connotation and as a metaphor. Let’s think of the Odyssey: embodiment of the mythical archetype of travel, thanks to the figure of Ulysses, a hero who’s experience and knowledge result from his endless traveling.

The original structure of the tale unfolds the fundamental phases of the travel: departure, transit, and arrival, despite Ulysses’ journey actually being a circular one, where the arrival corresponds with the departure. In this case, the circularity of his travel is necessary to comprehend how the hero returns home – after years of struggles – wiser and improved, his own identity strengthened.

In Ulysses’ case, the hero’s desire to return home implies the nostalgia of his beloved places and beloved ones, but most of all the necessity to find himself again. Considering the relevance of Homer’s poem within Western Classical culture, cinema couldn’t be indifferent to it. Both through direct representations of the hero’s life – for example “Ulysses” by Mario Camerini (1954) – but also transpositions which are indirectly tied to his character or to how the term odyssey has taken on to our daily lexicon, cinema has emphasised new and meaningful aspects of the poem. An absolute masterpiece is “2001: A Space Odyssey” by Stanley Kubrick (1968).

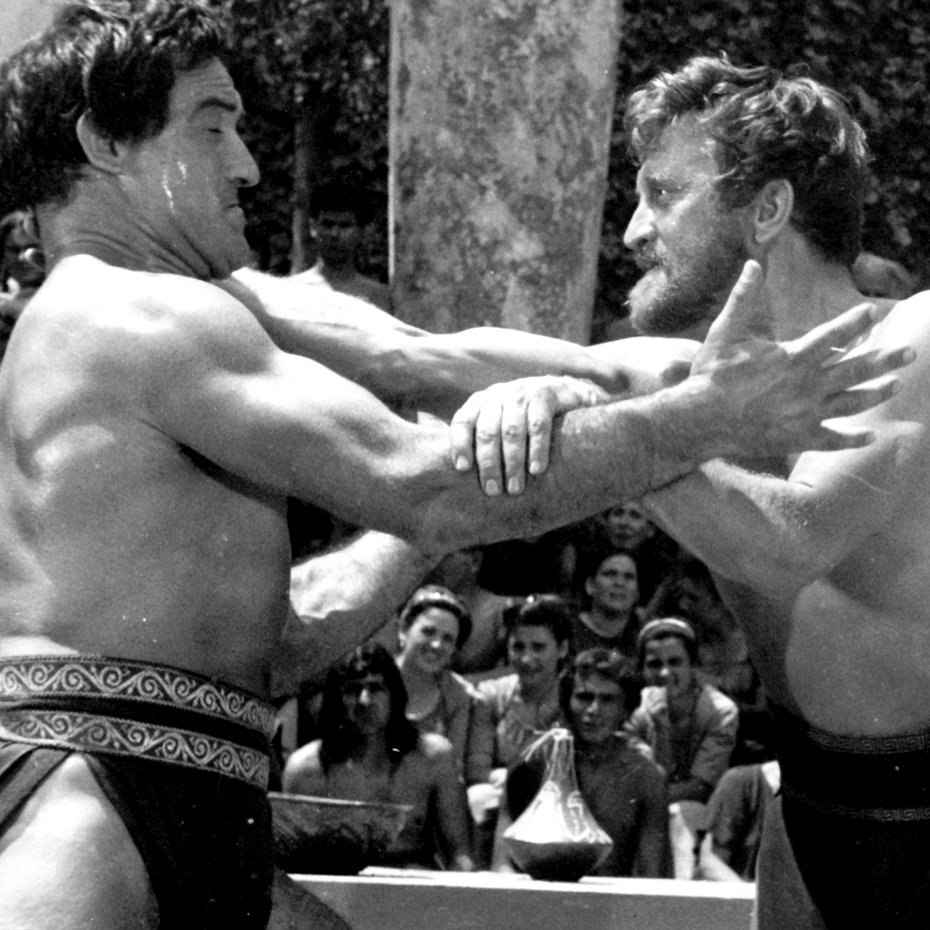

“Ulysses” by Camerini is also the first example of a blockbuster of Italian production, coproduced by the couple Ponti - De Laurentiis, along with Paramount. It was the most expensive film ever produced until then, and featured an international cast that included Kirk Douglas, Silvana Mangango – who was also De Laurentiis’ wife – Anthony Quinn and Jacques Dumesnil. Camerini chronologically deconstructed Homer’s tale, developing the story through flashbacks. In the film, Ulysses appears as disdainful towards any form of superstition, often guilty of pride, torn between the thirst of the discovery and the desire to go back to his home, Ithaca, and find happiness next to his wife and son he had left as a kid.

The director gives a very bourgeois reading of Ulysses’ story, in which the only possibility of certainty is the one you can have within your family. The sirens’ song in which Ulysses hears, for example – disguising the voices of Penelope and Telemaco inviting him to stop his travels and return home – is meant to highlight the feeling of safety that only family can give.

A brilliant idea was the one of casting Anna Mangano both as Penelope and Circe: austere and beautiful, covered in provocative peplos, the actress managed to instill completely opposite traits in the two characters. Very familiar, pure and reassuring the first, sensual but cold the second, a seductress that held Ulysses with the weapons of pleasure, preventing him to go back to his bride.

The involuntary journey, that – very much unlike Ulysses’ one – forces entire families to migrate in hope of finding a better future was a recurrent theme in the period preceding American prohibitionist, after the economic crisis of 1929. The great depression that followed the crash of New York’s stock market brought many to poverty and caused many families to migrate to states such as California, more fertile and with a milder climate.

“The Grapes of Wrath” (1940) – movie by John Ford – is the story of one of these families, the Joads, that from Oklahoma start a journey of hope towards the green valleys of the Pacific Coast. The new life that awaits the Joads though – just as thousands of other new poors – proved itself to be less ideal than expected, due to the arrogant and exploitative ruling class.

Based on the famous namesake novel by John Steinbeck, Ford’s film is an incisive cinematographic version of it, despite lessening the issue of class conflict and mitigating the end, making it more optimistic. The same optimism injected to the movie by its director marks its biggest difference with Steinbeck’s novel: darker, hopeless and – in some way – more militant.

For example, Tom Joad – the main character, played in the movie by actor Henry Fonda – in the book separates from his family to embrace the cause of the migrant workers and become an activist trade unionist, while in Ford’s movie he accepts to be on the wrong side, tolerating the serious injustice he witnesses.

Watching “The Grapes of Wrath” the collapse of the American dream becomes evident, its values torn down by the violence of capitalistic laws. Regret and nostalgia for the past prevail and in the end – in spite of everything – family’s unity triumphs. The original values American values can still

represent a barrier against the collapse of a life system and the progress of a new ruthless capitalism, if seen through the eyes of the mother, in this case.

The beauty of this film is emphasised in numerous scenes of great intensity: the wind that blowing dries up the fields and welcomes Tom at his return home when – after four years in prison – he comes back to find no one but the old pastor Casey (John Carradine) that has since lost his calling. The tale of possessed Muley, a farmer that – his home destroyed and his family gone – has stubbornly decided to stay and die on his land. The whole film is the perfect iconography of an era, so much so that if we confront its images with old photographs of the time we realise how much John Ford was able to portray a reality through his astonishing photography.

Moving to a more individualistic and introspective dimension on the theme of the travel, it is interesting to see the vision of director Wim Wenders, paying particular attention to “Alice in the Cities” (1972). The film, with “The Wrong Move” (1975) and “Kings of the Road” (1976) is part of Wenders’ “Road Movie Trilogy”. All this movies are characterised by having as a main character a lonely man that starts a journey. They feature characters moving along outskirts areas that reflect an inner separation, a theme that he will take on again a decade later, with the famous “Paris, Texas” (1984).

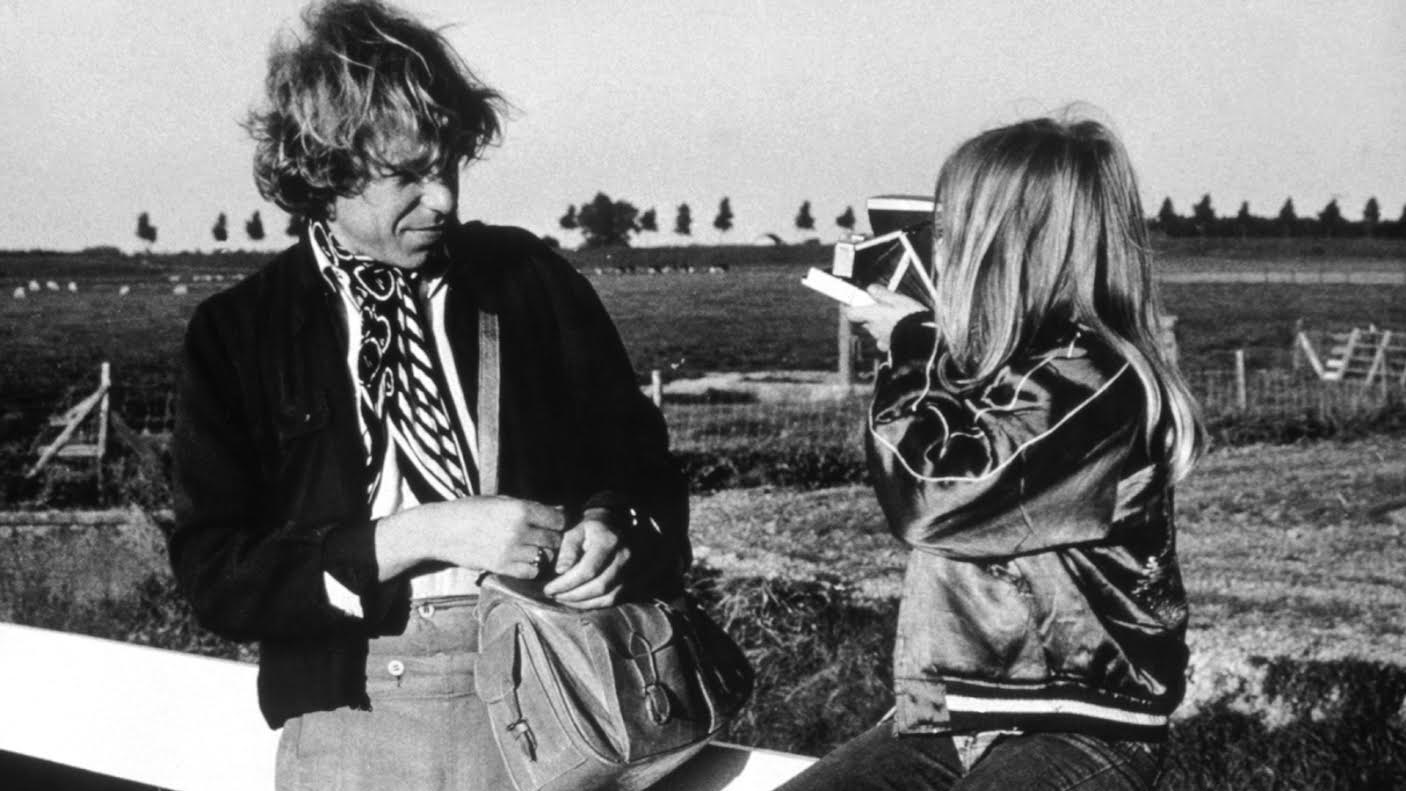

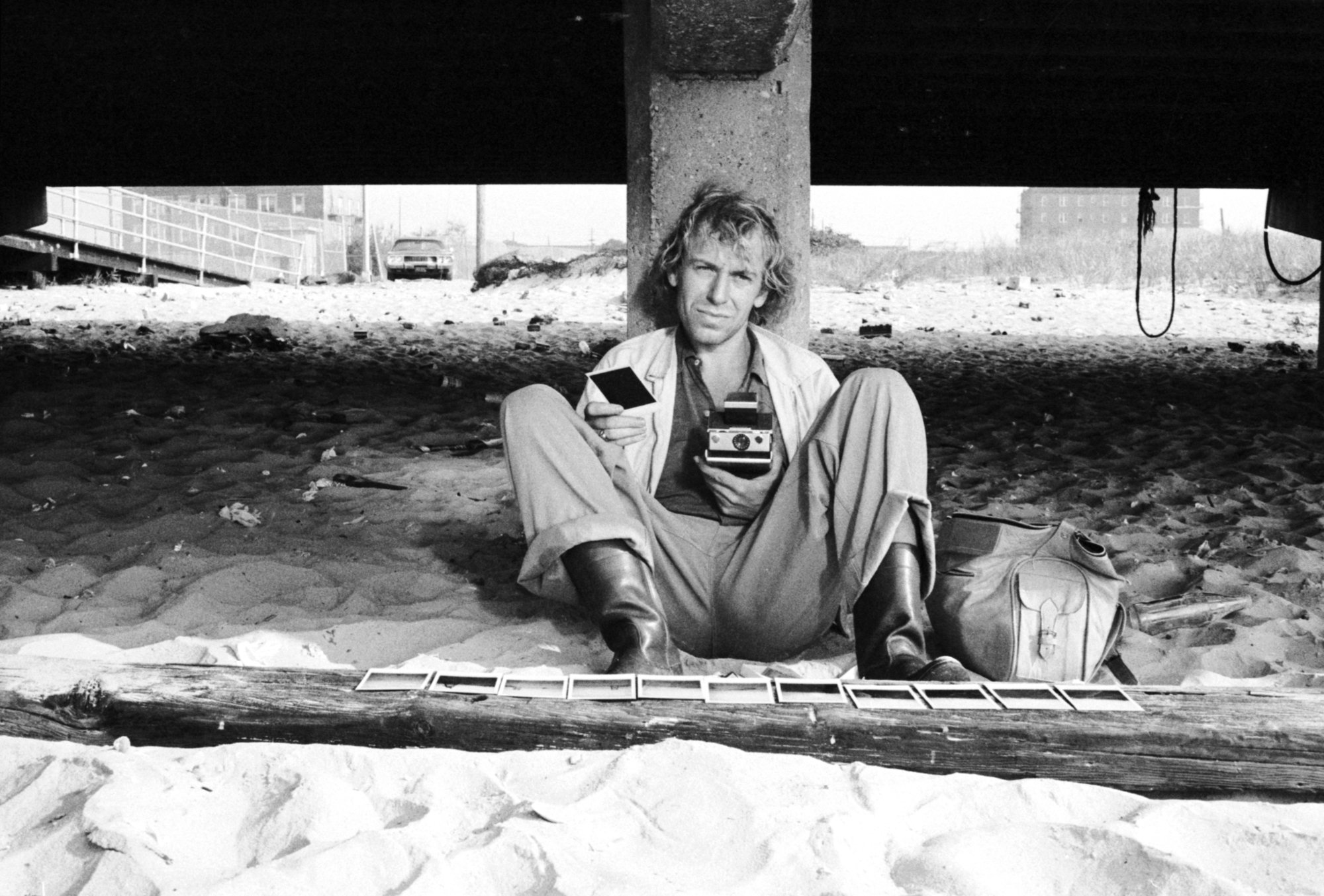

Felix Winter is a German journalist with a Rock’n’Roll look, that travels to the US to write a reportage on American cities. Once he is there though, a profound creative crisis blocks him completely and he simply capture lots of different scenarios with his Polaroid, resulting him to be fired by his exasperated editor.

Returning to Germany he meets Lisa, a woman that entrusts him with her daughter – Alice – asking him to bring her to Amsterdam where she is supposed take her back. This doesn’t happen and Felix and Alice find themselves alone, searching for the child’s grandmother.

The film is divided into two sections: before and after the protagonist meets Alice.

In the first part of the film the themes of knowledge and time prevail. Felix is obsessed with his photographs, he shoots hundreds of them, hoping to obtaining a proof of his own existence. Unfortunately each photograph also represents a disappointment for the journalist, as it is “never the same as to what you see”.

The second theme is indeed travel. Felix continuously wanders through American cities and his journey with no purpose or destination almost is an allegory of modern life. A timeless journey – because there is no growth in Felix’s inner life – during which his existence develops in a colourless, anonymous manner. Finally, the journalist’s existence shifts when, while waiting for the plane that should take him home, he meets Alice, abandoned by her mother. Felix’s world is completely upset by this and when he realises that the mother is not in Amsterdam waiting for her, Felix’s first instinct is to leave the kid to the police. In front of Alice’s tears though, the journalist decides to start a new journey with her, seeking her grandmother, even without knowing the woman’s surname or the city in which she lives.

That’s when the theme of travel comes back, renewed: Felix no longer wonders without a destination. There is a goal now, the search for Alice’s grandmother, even if so difficult and vague, lacking solid proofs, acquires a meaning, and so Felix’s life does as well. Slowly the relationship between the two changes, the initial mutual annoyance develops into a human relationship of friendship and affection.

At the end of this journey and because of his encounter with the child, Felix rediscovers himself finally becoming part of a world in which he did not feel welcomed before.

Crucial is the last scene that sees the adult and the kid on a train, embarking on a journey toward long sought affections, with the camera moving away and broadening the image from the first close-up to a wide shot where the two characters are nothing but small dots, lost in a natural view.

Instead,“Stand by me” by Rob Reiner (1986), starts with a flashback. Film in which the analogy of travel conveys the growth of his main characters, the narration begins from a crime news read by Gordie Lachance a successful writer – that starts remembering when at thirteen years old, he first saw a dead body. From this memory starts his journey through time that will project him – and the spectator – from a small town in Oregon right to the summer of 1959.

Four teenagers, each one with a difficult background, learn that there is an abandoned body in the woods, at about fifty kilometers from their town. They decide to start a journey of discovery that will take them to live numerous adventures before arriving to their destination, where a final fight with some older teen- agers for who gets

to take the dead body unfolds. Through the theme of travel, the director explores another fundamental theme: friendship.

A friendship that – despite the passing of time – is still well alive in Gordie’s adult mind and so alive that it pushes him to think about and to narrate the same extraordinary journey he and his friends had undertaken, many years before, through a path that represents the inner growth.

The four boys are forced to overcome a series of obstacles that catapult them into adulthood, such as the responsibility of having to take decisions alone, sexuality and the discovery of the difference between myth and reality. They deal with the fear of the darkness in the night, a classic setting of childish obsessions, overcame by spending the night together around a fire, talking about themselves and their experiences, acquiring independence from the protectiveness of adult figures.

They experience death, a presence that characterises the whole movie since its beginning, when adult Gordie learns about the passing of an old friend of his.

The boys’ path follows the train rails, which is an important element as the trainin the history of cinema – has always represented the classical iconography of travel.

In the end of the movie, the real encounter with death represents at the same time the end of the journey and the beginning of a new life for the protagonists.

With the discovery of death comes the boys’ awareness that something inside of them has ended forever and that, from the ashes of their childhood, something new is born that will project them into a world that they hadn’t known of, just yet.

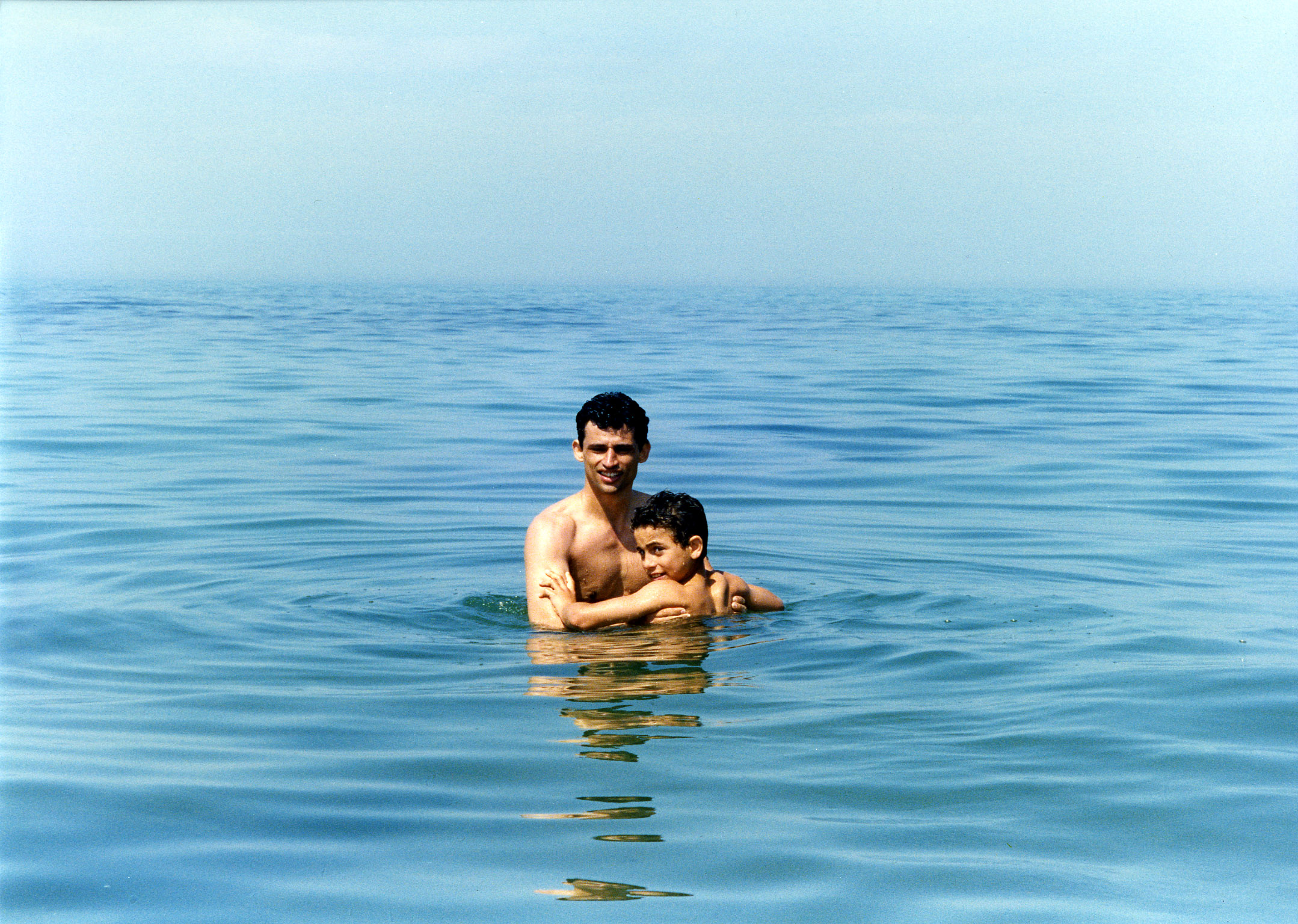

The steady and conflicted relationship between childhood and adulthood is the focal point of another film by Gianni Amelio, revolving once again around the theme of traveling: “The Stolen Children” (1992).

In Milan Rosetta – 11 years old - is forced by her mother to prostitute. Luciano – her younger brother – would want to rebel but is incapable of doing so. He instead isolates himself in silence on the house’s balcony, while his sister welcomes men in her room. After the kinds’ mother get arrested, the two of them are sent to an orphanage, escorted by policeman Antonio (a charming Mediterranean Enrico Lo Verso) where – with the excuse of bureaucratic difficulties – the Director refuses to accept them.

This is how the trio starts wandering through Italy, ending up in Sicily, searching for an institution that would welcome the brothers. During this journey, the initially hostile feelings of Rosetta and Luciano towards Antonio turn into affection, until their relationship break the boundaries of their institutional roles. Because of that, Antonio gets accused of kidnapping the minors.

The journey the main characters undertake from Milan to Sicily is a journey throughout the contradictions of Italy: its poverty and richness, its environmental decay and works of art.

It’s a journey of conquer: for the policeman the ability to overcome the institutional aspect handed to him and grow fond of the kids; for Rosetta and Luciano the conquest of a childhood never lived.

In the whole movie the theme of a denied childhood manifests itself in girl’s toughness and in Luciano’s mutism – which he often hides behind – in his asthma crisis and in the extremely harsh relationship he has with his sister. Only at the end of the journey they acquire their true childlike reality, when Rosetta’s face finally opens up in a smile and Luciano begins to feel affection.

The physical travel through real places is, in this case, a metaphor for the characters’ inner journey. Antonio, then, emphasises the palpable social and civil decay in Italy. In one of the most intense sequences of the film, he decides to stop in his town in Calabria, where his sister runs a restaurant. Here, during a party for a holy communion, emerges the prude conformism

of a society that cannot accept a little girl, once they recognise her as the baby-whore of which the papers had published a picture.

Antonio’s character embodies the distortion of a society that has cut the bridges with its own peasant culture, for the sake of an enrichment happening through varied, mostly illegal ways.

The look of the director is at the same time extremely critical towards society and filled with love for the characters that he presents us with.

In “The Straight Story” by David Lynch (1999), the tale of a lost and grieving town – where the prejudices and bigotry are hidden under an aura of apparent calmness and tranquility – is the dominant trait of the narration. In a small village in Iowa lives the old Alvin Straight with his daughter Rose, who’s mostly thought of as mentally retarded.

When Alvin learns that brother Lyle – who lives in Wisconsin and whom he hasn’t heard from in years – has had a stroke, he realises the futility of the reasons that has kept them apart and decides to go visit him before he dies.

But how can he get there? Alvin is almost blind and has leg problems that prevent him from driving, so he decides to travel on the only vehicle he is able to drive: a lawnmower.

David Lynch – author of numerous films that dig into the dark side of the human mind – tells an apparently minimalist tale in a setting, that of the Mid- west, where the majesty of big places speaks of peace and tranquility.

The movie is inspired by a true story and is enriched by the extremely good portrayal

of the main characters: eighty yearold Richard Farnsworth (Alvin) – here in his last appearance on the screen after having spent a life as a supporting actor – and Sissy Spacek, perfect as Rose.

Despite a beginning that would lead to assume an imminent tragedy to come, the tale turns quiet, immersing the viewers into the calmness of the town, its cultivated fields, its idyllic landscapes and the slow passing of its citizens’ lives.

But the one of Alvin Straight is in fact a painful life, from loosing his children to witnessing the tragedy of war. That is precisely why – at the news of Lyle’s illness – Alvin feels the need to reconcile with him, and with life, before he dies.

“The Straight Story” is a classical road movie, but it’s also really odd as it subverts the genre’s overall rules. There is no hero leaving to go on an epic venture, nor a desperate man running from his past. Instead, there is a common man that has comprehended how – to close the chapter of his life – he has to tie back the threads that had loosened along the way.

Lynch’s film is a sort of millennial Western, in which we find lots of stereotypes of the genre: the immensity of the American landscapes, the nights around a fire, the old cowboy that – checkered shirt and hat on the head – jumps on a horse and starts his journey.

In every era and at every latitude, the term travel has always been used to describe a much wider concept: the one of life – from birth to death – or as a metaphor to illustrate the passage from earthly life to a hypothetical after life.

The duo of life and death is constantly present when speaking of travels: the departure represents the birth towards a new life, leaving behind the experiences lived until then.

The destination, then, marks the definitive death of the old self and the rebirth of a new man.

Not necessarily best or worst than the previous one.

Just different.