Precision (and Exhibition-Making)

Words by Judith Clark

The theme is a wonderfully contentious one curatorially. Precision is, strangely, within the discipline of curating dress, synonymous with accuracy. It is the difference between the two - what gets lost between them - that is so interesting. To be ‘precise’ whilst curating dress might be about getting the facts right - date, provenance and so on. To be ‘precise’ mounting the dress might be about best supporting it, with the expected amount of care, according to the precise rules of conservation. We rely on this precision to get our bearings in museums - we rely on the facts, we rely on the best protection of the garments for posterity.

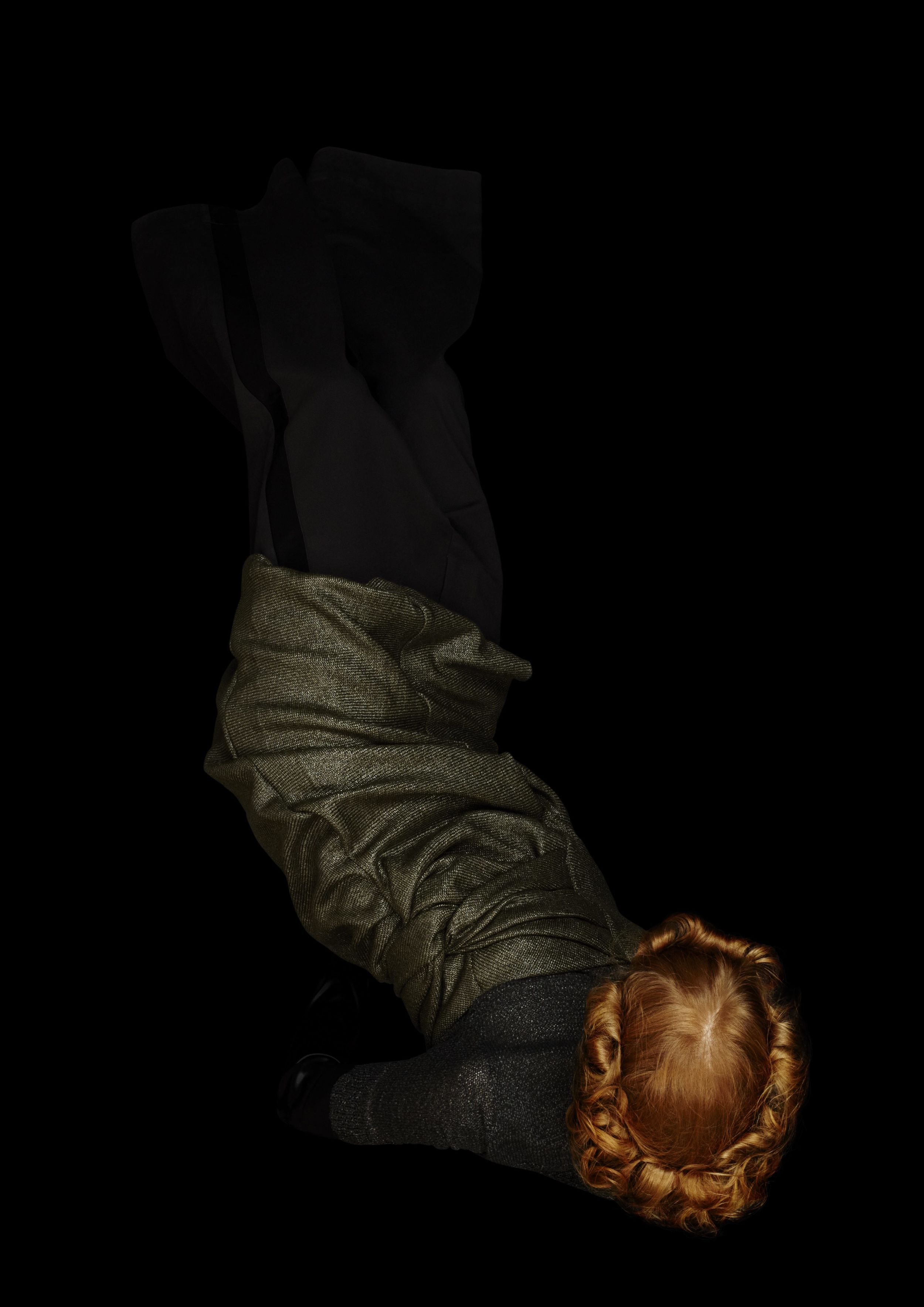

There is spillage however from this essential practice that is the point of this essay. What has happened is that there is a notion that this ‘precision’ can extend to the exhibiting of those same objects, that there is an imaginary right and wrong - one that more than another reflects the object’s reality and its very materiality.

It is very difficult to get exhibiting fashion wrong as it is so profoundly linked to the body; so it would be very hard to exchange or confuse fashion with any other kind of object. An understanding of its basic use and immediate context is almost guaranteed, unlike many other applied arts. Our bodily functions have persisted across time but not our cultural assumptions. So are we communicating strangeness or continuity, for example; and where is the visitor invited to suspend disbelief, and on which side of the exhibition threshold - the door to the museum or the plinth? Is the precision about the best communication of the parameters, the rules of that suspension?

One of fashion’s great qualities is the sartorial collage it creates from historical borrowings. So which moment is privileged in our precise brief? or is it about collage itself? and how is the present (our own perspective) allowed into the equation? The creative consultant to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the late Diana Vreeland, would have said it gave it its vitality and desirability, that it was essential. Her critics would have said no, that it was corrupting to an idea of a precise past. She was famously precise (tyrannically so, sending assistants on endless quests) but famously not ‘accurate’. But according to which brief?

Exhibition-making has been discussed at length within art curating and the wrangle has always been between artist and curator/designer; and where the experiment is: within the exhibition, in the art itself or within the way it is being re-presented. Whether, for example, by theming works of art, their original content - and their originality - is being diluted. Accuracy is linked tointention, the artists first intention. In dress the designers intention is associated with the first (now catwalk) presentation, the first wearer, a complete look; but we know that does not reflect how the object is worn and re-styled and worn out.

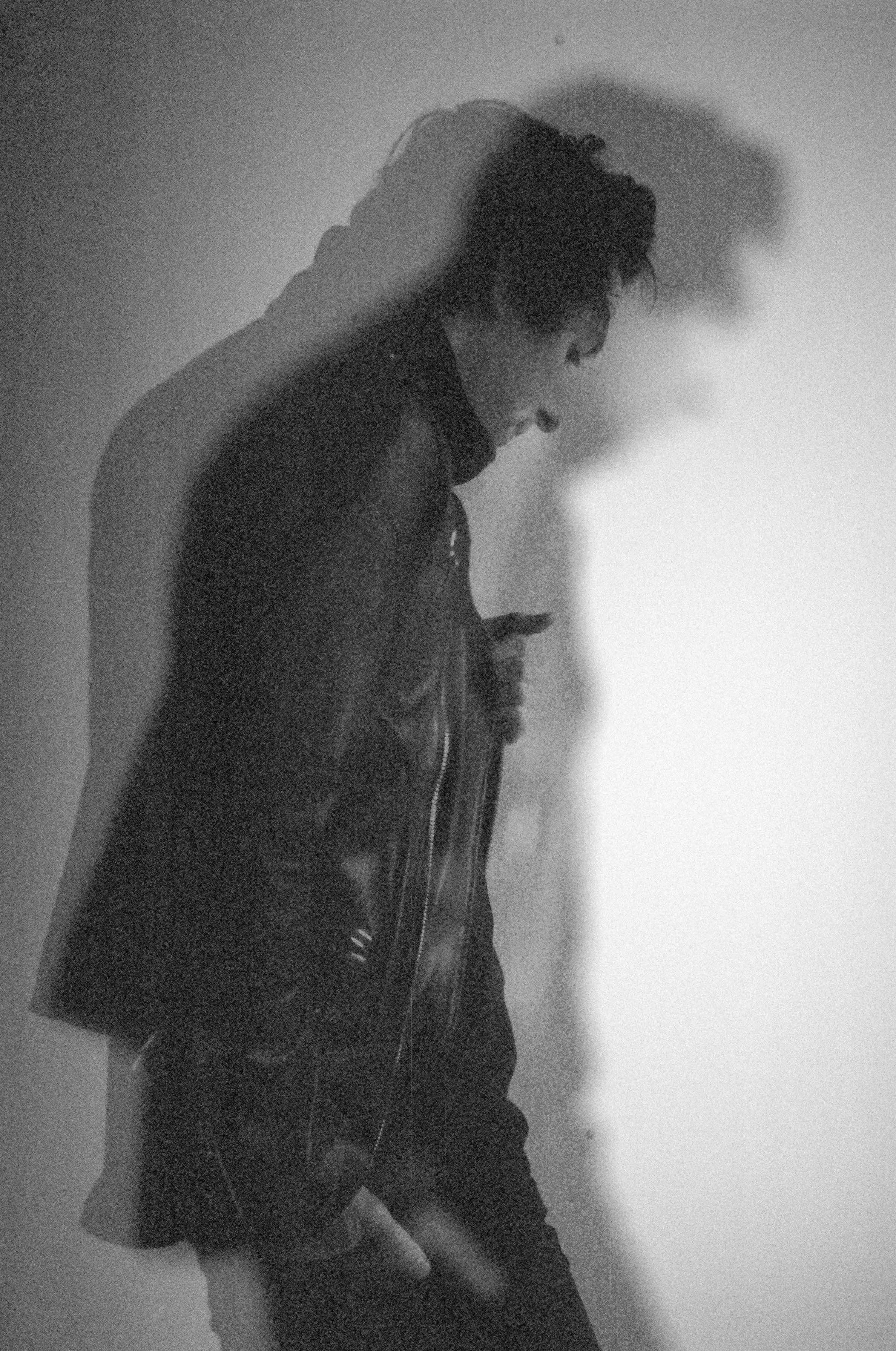

The exhibition, like the essay could only ever be a suggestion, an idea about putting a series of objects, like words, together. Which version of reality is being staged and why does it matter so much? There is no accuracy, there are only debates about accuracy and what it might be.

Perhaps we should bear in mind that the most common definition of the word ‘Anachronism’ - so essential to dress and the curation of dress - is: “ an error, assigning a thing to an earlier or (less strictly) to a later age than it belongs to” (Chambers Dictionary).

And we could also bear in mind the uses of error in the exhibiting of dress. The fear of excess in exhibitions is similar to the fear of excess in dress itself - that at any moment one might fall into the wrong kind of display. But this anxiety may be the biggest threat to this discipline.