Balthus Retrospective in Rome

Words by Sarah Millar

“Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault.” O.W.

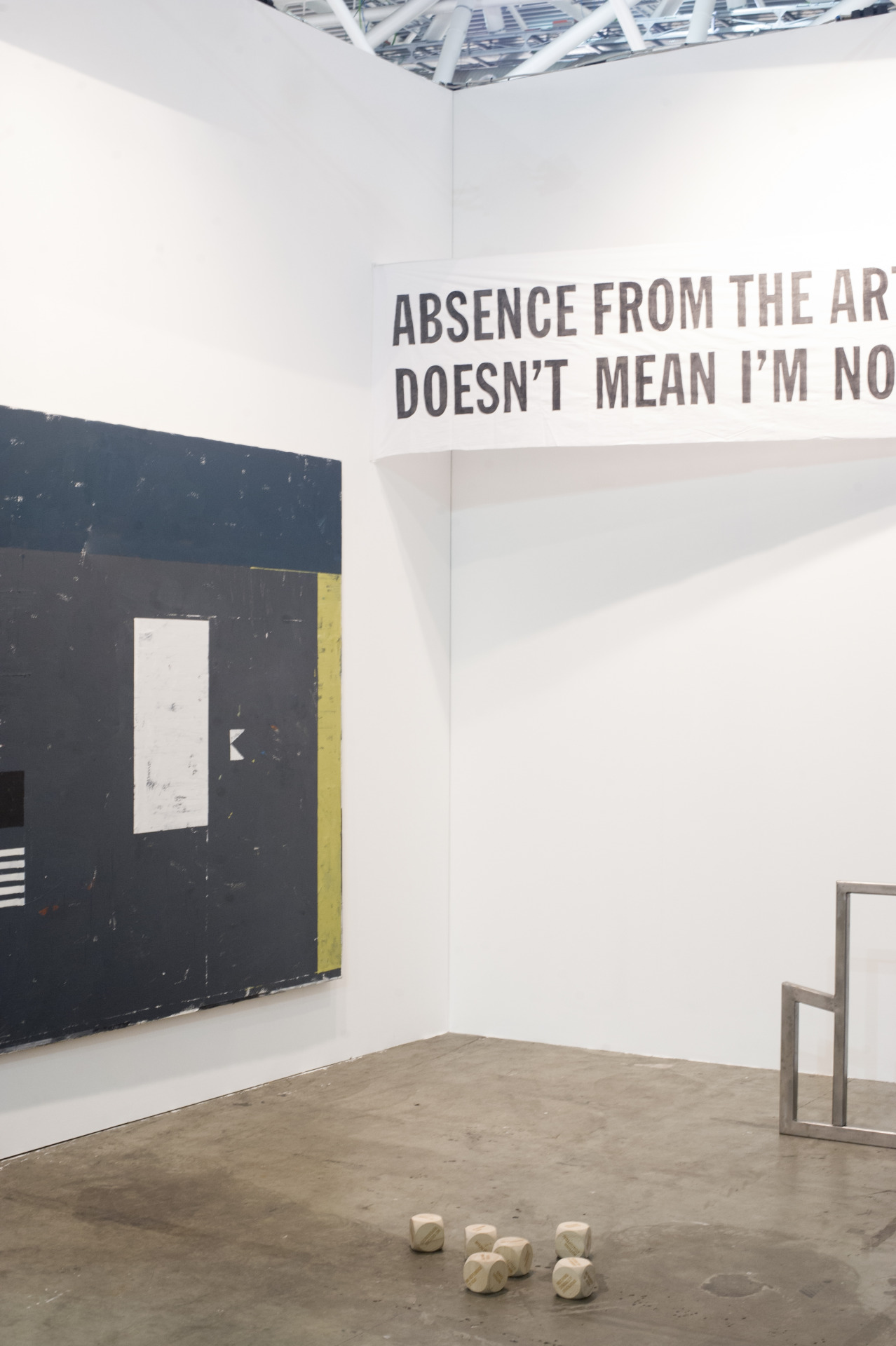

The art world prides itself on inclusivity these days. Indeed, the boundaries of the term have been stretched so far beyond their elemental elasticity that some may argue it’s all begun to lose its shape. We approach preserved sheep with a yawn, we nod thoughtfully as Tilda Swinton nods off, we’d see play-doh through the kaleidoscope of high art if we found it in a white cube. In this age of seen it all, done it all, seen it some more, we often find ourselves wondering if we’ve quietly entered either a post-shock stupor or a sycophantic circle jerk. Ironic then, isn’t it, that a surefire way to spark an incendiary debate amongst gallery goers, academics, critics and the gen-pop alike is to hang a show of entirely figurative art, painted in the most traditional of media, by a highly skilled hand that tended to his opus for eight hours a day until his last? Fancy a bit of intellectual ballyhoo? Bring in Balthus, he’s always good for it.

Fifteen years after his death, the inscrutable, ‘anti-modern’ master is set to be recognized in the Italian capital with a major monographic exhibition set in two locations, Scuderie del Quirinale and Villa Medici. It will be interesting to see if it will stir quite such a provocation as did the last blockbuster showing of his work, or if locals will meet the paintings with a ‘when in Rome’ shrug. Either way, it seems fitting that the Roman ode to Balthus, which opens October 24th and runs through January 31st, will be split between two sites as his legacy is one heavily punctuated by duality. The anti-modernist lauded for his radical realism is at once loathed for his stylistic conservatism. The modernists loved to claim him as one of their own, yet Balthus refused to pledge allegiance to anyone or anything but his own myth. Critical, and public, reception to the divisive artist is, now more than ever, split firmly between two camps. There are those who admire and those who abhor, those who sing an elegy of insight and those who sound the alarm of exploitation. There are those who grant Balthus blanket impunity on the grounds of ‘high art’ and those impugn him unreservedly from the dizzying altitudes of the moral high ground. Is the disquiet Balthus’s subject matter stirs in the viewer to be condoned, or is the suggestion of depravity from whence it stems to be condemned? A few strokes of moral equivocality add such depth to a flat canvas, don’t they?

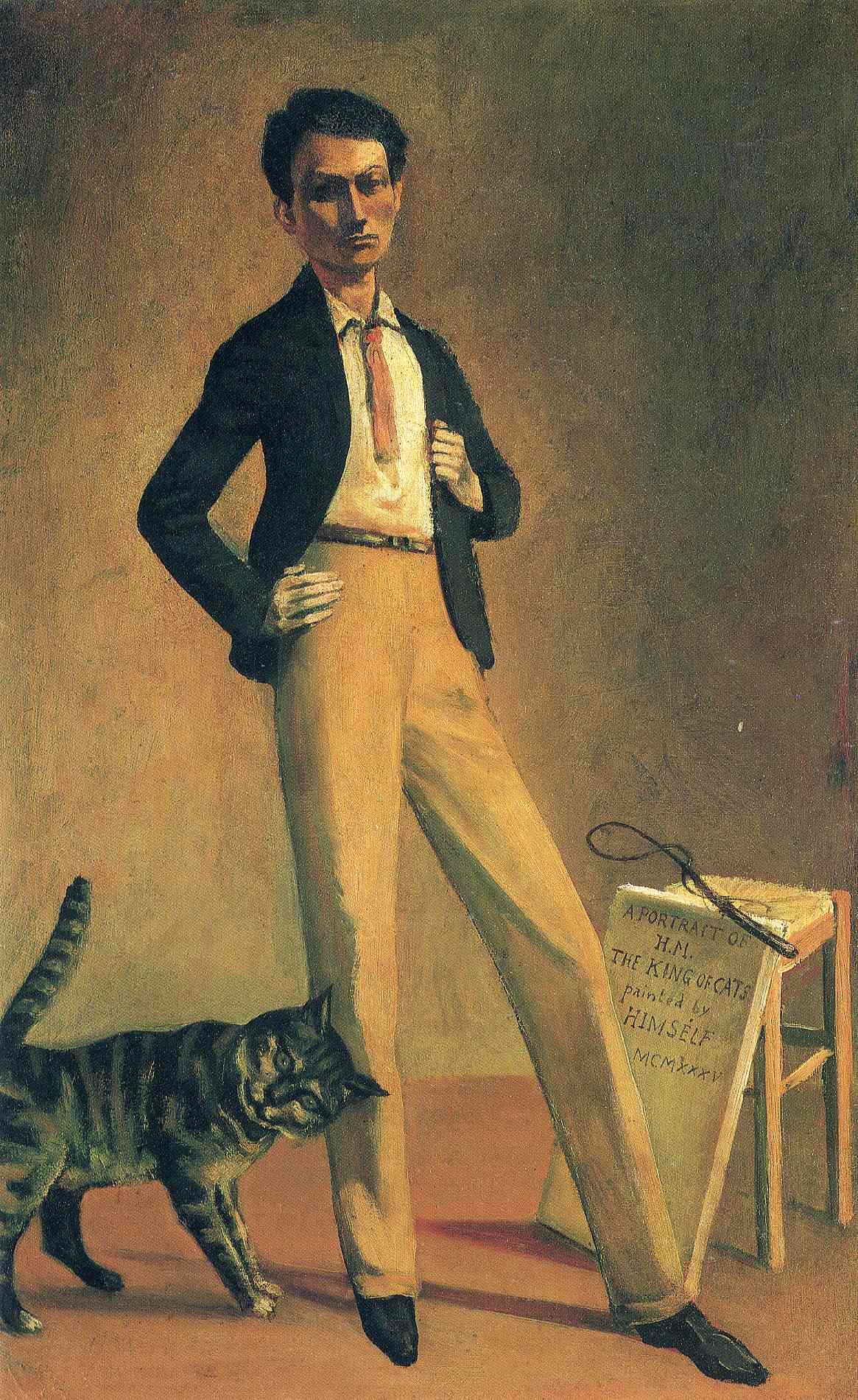

To quote the man of the hour, “Balthus is a painter of whom nothing is known. Now let us have a look at his paintings,” which seems a good place to start.

Though Balthus reached artistic maturity at a time when many of his contemporaries were following a trajectory of abstraction, his style is strikingly dissimilar, old fashioned even. It could be posited, of course, that Balthus’s tenaciously classical style is biographically moored; that the artist’s refusal to hop aboard the train towards abstraction is reflective of the man’s reluctance to keep up with the times. After all Balthus spent much of his adult life tucked away in various chateaux, mansions, and fairytale castles, crafting his own legend, wearing cloak of privacy with a flourish, reveling in the romance of clandestinity. So perhaps in the grand tradition of the canvas he sought sanctuary from the modern. But did he? Yes, we can home in on the influence of Courbet’s realism, Modigliani’s melancholic faces and Ingres draftsmanship. But there is also evidence of Neue Sachlichkeit detachment in mix, a subtle nod to Cubism by way of flattening the pictorial space and human form, and Balthus’s use of symbol and leit motif draw their own parallels to Surrealism. So perhaps by insistently retaining the figure in the age of progressive abstraction, by seceding from the tract, by rejecting the avant garde, Balthus was, in fact, Modernist by default. Could it be that Balthus’s radical conservatism was simply a ruse, then? That his unrelenting realism was just veneer beneath which he exercised highly controlled alchemy of stylistic amalgamation? No answers are offered; tidy conclusions are never Balthus’s endgame.

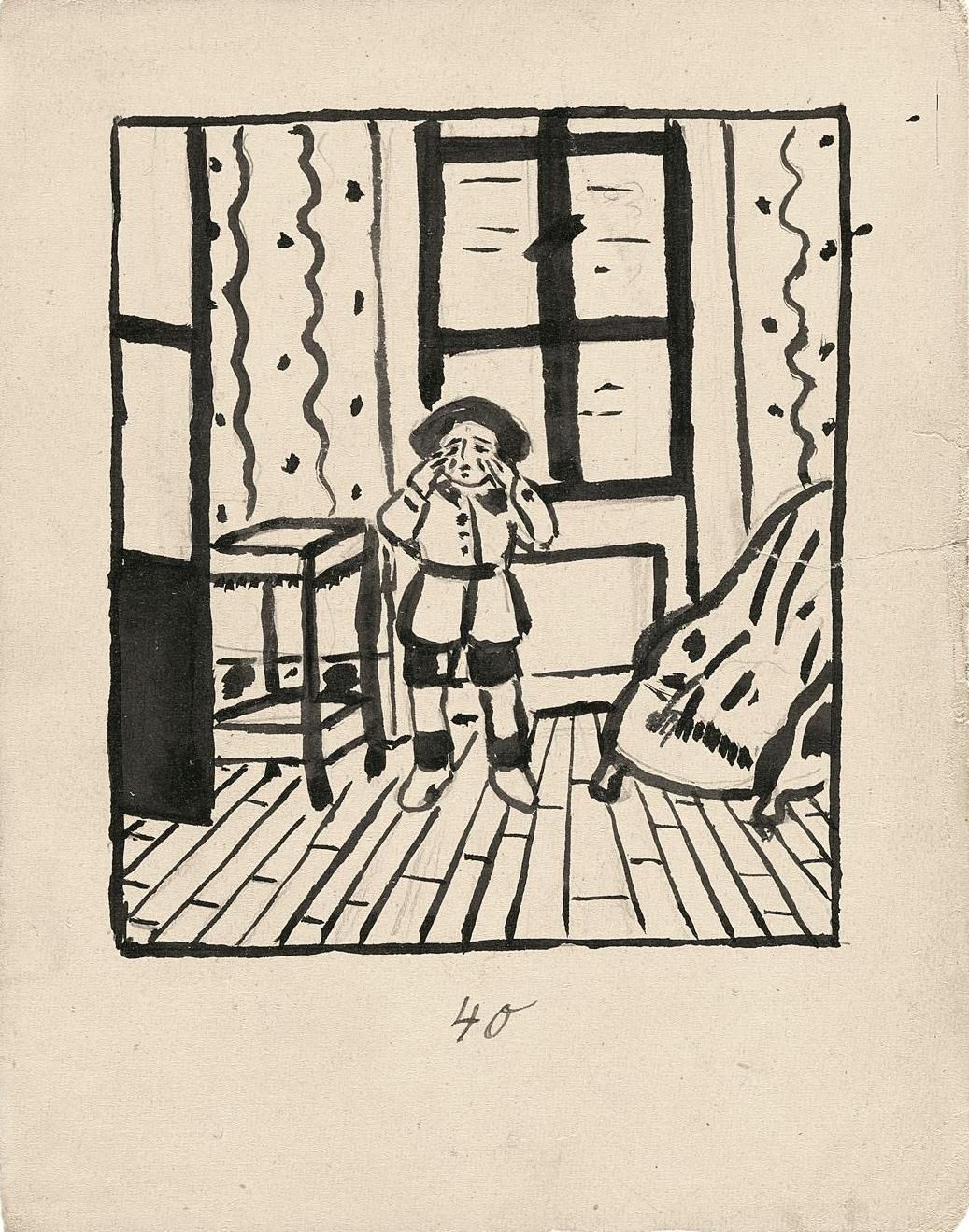

On the topic of personal provenance, worth mentioning here is a must see piece in the exhibition: Mitsou. This incredibly potent little book of pen and ink drawings was published when Balthus was just thirteen by his mother’s lover poet Rainer Rilke, who also penned its preface (“...else by their hostility or their fear they will merely measure the distance that separates them from us, and relations between us will consist solely in that.”). The book is comprised of a series of drawings that the artist created at the age of eleven when his beloved cat Mitsou went missing. This sad, and almost chilling, depiction of solitary boyhood is astoundingly precocious work for a tender age child, not only for the precision of its execution (which recalls some equally severe woodcuts of the German expressionists) but also for its prescient exploration of themes which will become fundamental tenets of his adult work. For not only are these drawings fascinating and dark in and of themselves but they can also inform our reading of Balthus’s depiction of, and fascination with, the dawn of adolescence. Balthus’s girls, for example, are never smiling, there is a very “grown-up” heaviness to their expressions, they are deeply pensive. Perhaps behind the eyes of these young girls Balthus found the sadness and solitude he experienced himself as a child. Perhaps their vulnerability and exposure reflects his own; his talent revealed too soon, laid bare for scrutiny before he knew to cross his legs. But before delving too deeply into that fray, the thematic consistency throughout Balthus’s work is interesting to note, and also points to a certain abdication from the passage of time in a conventional sense. As does the fact that he was born on a leap day, which Rilke told him granted access “to a kingdom independent of all the changes we undergo.” At the time of his death in 2001, the man had only celebrated twenty-two birthdays. By the magic of this meta-physical measure, Balthus spent much of his long life a child.

And now on to the girls because never mind the cats, it’s the girls that raise the hackles. Balthus’s presentation of pre-adolescence clearly stirs discomfort in his viewers. But perhaps it’s all too easy to jump to puritan outrage and feminist disdain for their exploitative nature. A sexual undercurrent is certainly present, and at times purposely so. Are these the unguarded moments of the innocent, though, or something bolder, precocious, self-aware? There are layers of visual tension that warrant more than a fleeting glance and reactionary contempt. It’s Balthus’s marriage of his very conservative style of painting with an insistently provocative subject matter that heightens the tension in a very subtle and interesting way. There is a stillness to the canvas, moments are frozen, preserved. The children in Balthus’s paintings tend to occupy that precariously suspended space between innocence and its loss. They are held here, in the pause between one breath and another. They are disengaged, slightly sulky, restless, lost to either their daydreams or their brooding; all a bit melodramatic, all a bit familiar? With elegant, muted tones, Balthus paints the grey areas. With a palette at once wan and somehow radiant, Balthus reflects the ambiguity of this fragile age.

Throughout his life Balthus denied the sordid rhetoric surrounding his work (with the notable exception of The Guitar Lesson, the pornographic nature of which he admitted and wrote off as youthful folly), lobbing the onus of responsibility for such notions right back onto his indignant critics. “The problem is the viewer’s longings and interests, not mine.” He shared Wilde’s assertion that art mirrors the spectator more than it does life. Balthus toed a moral tightrope to be sure, but oftentimes any hint of eroticism in the paintings is undermined by an almost eerie compositional neutrality. Arms and legs are arranged to create certain angles and special order in the same way that furniture is used to articulate the architecture of the field; emphasis is evenly divided between the two. The aforementioned silence also impacts here, quelling any suggestion of the passion that tends to underpin longing. The girls are perhaps unclothed, exposed, partially nude, but their bodies aren’t starkly, violently naked the way they might be in a Spencer or a Freud. Some might argue that the very fact that Balthus focused so much of his life’s work on painting prepubescent girls is cause for concern enough, that at best he was a degenerate voyeur, at worst a pedophilic predator. Others might hint at the hypocrisy of a society that worships the cult of youth, capitalizes on its over-sexualized teenyboppers, child stars and pageant queens yet bristles at the mere flash of white underpants. Yet again, we are offered no answers. Balthus instead presents a visual challenge that we are left to reconcile.

Oscar Wilde suggested that there is no such thing as a moral book or an immoral book, that books can simply be well written or poorly written. Perhaps the same applies to art. Perhaps we can save ourselves the debate and portentous dialogue and just admit that Balthus was a good old-fashioned painter. How frightfully radical. Love him or loathe him, go take a look. The exhibition at Scuderie Quirinale will be a complete chronological retrospective whilst Villa Medici will feature works created during his time as director of the French Academy in Rome.