Issue 10: Compulsory Party / Passive Aggressive

A FEMALE PERVERSION

BY PHILIPPA SNOW

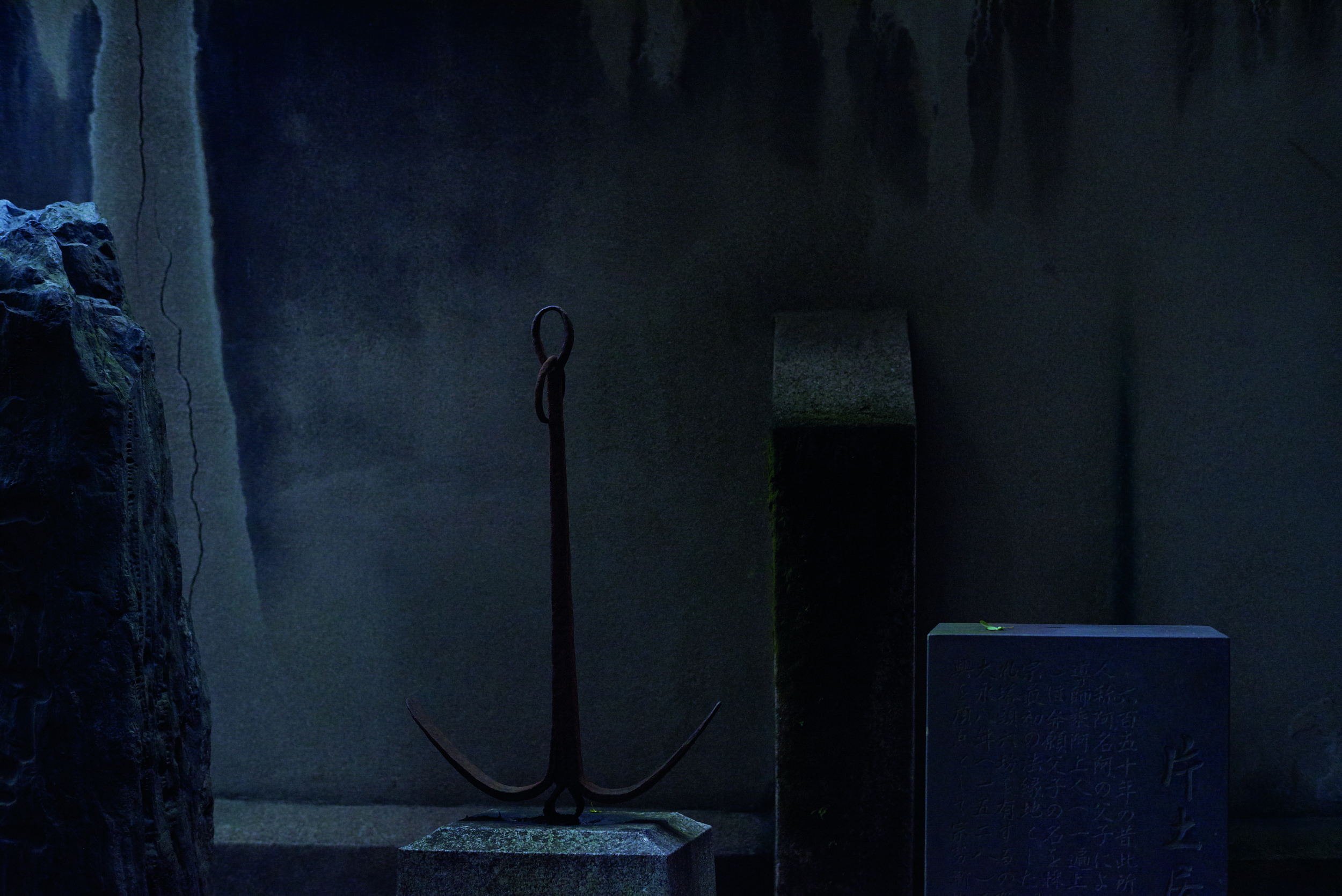

PHOTOGRAPHY BY GIASCO BERTOLI

STYLING BY MORENO GALATÀ

The brand-name was Broadway Jet-Dry, two-thirds of it carrying their own unfortunate connotations of glamour and worldly sophistication — connotations which became unfortunate, anyway, given the circumstances surrounding the product’s brief appearance in the papers, at which time the phrase “Broadway Jet-Dry” became synonymous with a number of other phrases, as well: with “cut from tip to palm,” or “rotten finger,” or “amputated at the second knuckle.” It is curious how quickly a trend starts up, and how violently it spreads — as gangrene, a bush-fire, the venom of a snake in the body of a child — and curious, too, how happily we are subsumed by it, sacrificing ourselves in increments on the altar of many very pretty little things. In this case, the trend was not only a trend, but also a biohazard: Sarah Greenaway from Pontypool, South Wales, had dragged Broadway Jet-Dry’s name into the tabloids when use of the nail-glue had rotted her finger straight down to its bone. “All [she] wanted,” she’d told the Daily Mail, “was for [her] nails to look nice.” This was not, of course, what happened — what happened was that at first, the finger in question turned green, and then it turned black; then Greenaway found herself rushed to the E.R., where surgeons used sharp, Ballardian tools to excavate the interior of her hand, which had, by then, filled with something unspeakable. It was an injury, you would assume, that would have a particular smell. It was grisly. Photographs of the sutures on her finger look rather like the spokes of a pair of false lashes or, fairly aptly, the spokes on the ‘mouth’ of a Venus Flytrap. Men are from Mars, and women from Cronenberg movies. Something ostensibly beautiful had, in a very short span of time, adopted a horror-film quality, and the ruined finger invoked other kinds of films, too; other references, like the manicure top coat speech in American Hustle:

“There’s this top coat that you can only get from Switzerland and I love the smell of it. I don’t know what I’m going to do because I’m running out but I love the smell of it. It’s like perfumey, but there’s also something rotten...Historically, the best perfumes in the world, they’re all laced with something nasty... Carmine...sweet and sour, rotten and delicious...Flowers, but with garbage.”

Flowers, but with garbage. Rotten and delicious. Lawrence’s hands and their delicate, ruby tips are practically bruising the monologue’s throat. If its metaphor has another, larger meaning in the movie (and I am certain it does, although I confess to being less taken with Hustle than many of those who saw it) it works just fine for our purposes, too — if Russell can play with the minds of his actresses, we can play with the core of his texts. What I would like it to mean is this: that the very act of making oneself into something beautiful is, occasionally, an ugly, stinking hazard, or maybe that betrayal by beauty is being betrayed by a mostly-feminine labour. This is a female perversion; a female injury. There is no evidence to support my thesis, but I picture the manicure that Greenaway planned as looking like Rihanna’s, largely because Rihanna’s manicure — as I remember it in my mind’s eye — is flawless. The shape of the nail, beginning as teardrop and ending as dagger, is almost mathematically sexy. Nails to ruin a millionaire’s back, to scoop a bump, to claw at the eyes of some bitch in the club, to scratch a cheater’s Ferrari paint. Hers are nails for screwing, revenge, and power, the kind which comes from never having to lift a finger unless the wearer is motivated by passion or drive or desire. Rihanna, our gal’s gal, is aspirational for almost every woman alive, and so our most modern ideals of beauty and cool can only be built to reflect her; we dissemble, physically, in order to resemble, and lose ourselves in the action (or, in the case of Sarah Greenaway, we lose our fingers). As a piece of engineering, Rihanna’s hands are as perfect and all- American as the Empire State Building — those who fall when trying to scale her heights are merely the omelette’s broken eggs.

“Long-lasting gel manicures are beloved of celebrities including Victoria Beckham and Jennifer Lopez, but...[an] article [in the Huffington Post] cited two women who had developed skin cancer on the backs of their hands, allegedly caused by repeated exposure to UV lamps.” The message is clear: Victoria Beckham and Jennifer Lopez — as is true of Rihanna — are made from another, less fragile material, and death and disease approach them from different, more diffident angles. Latter-day photographs of Lopez will always captioned with, first, her age, and second, the caption-writer’s abject disbelief because we are used to seeing a normal human body behave with normal, human fallibility — “star style” tutorials for highlighting, contouring, shadow or lipstick will always fall short, because it will feel, at times as if we are aiming for actual stars. Buy your U.V. varnish from Dior or Chanel, says the Telegraph expose, to avoid the attendant cancer of the skin, a directive so closely governed by automatic assumption of personal wealth that it almost boggles the mind: would, anyway, if the reader did not know already that richness is next to Godliness or — to offer an honest alternative — being rich is like being God. Still, there are innumerable chances available to us provided we’re happy to simply play at being wealthy. Pontypool is three thousand miles or so from New York’s Broadway and has no jet-set of its own, but satisfaction is sometimes paid for in slim and inexpensive tokens. Carol Burnette and Liza with a Z, and the act of putting on the Ritz; the cream lamb’s-leather interior of a billionaire’s Gulfstream; a retail value of three pounds and twenty pence sterling; a cheapo resin’s acrid tang — all things in cosmetics, as in life, are delicately interconnected.

Aspiration draws atypical diagrams, tracing a flowchart from terminus “garbage” to terminus “flowers.” The business of beauty is, by its very nature, dishonest: its backbone is not made from bone at all, but from plastic, acrylic, synthetic or similar, trading on substitutions and fix-it facsimiles. Not for nothing are colour-copies colloquially known as “dupes”, and, as with every short-cut too good to be true, there are risks inherent (exampli grata: humiliation, amputation, death). That these risks are somehow more risky for the “dupes” among us — the poor, the less conventionally-attractive and, most importantly, our minorities — means that the line of beauty follows the line of life: it is ugly, unnatural selection. If, as Updike claims, celebrity is a mask that eats into the face, the same might also be said of artificially- altered beauty. Examine any person who has extensive plastic surgery in both their “before,” and their present-day “after” pictures, side by side, and their former features will often appear to have been subsumed entirely, like trees in a swamp, or like land in a rising flood. Doubt is a fundamentally human quality; self-improvement, in styles this radical, is a newer behaviour. Fetally smooth, preternaturally young, a face that constitutes radical or iconic architecture — viewed from the right angle, even the Chrysler building resembles a Botox needle, and given the means, it’s easier to sneak into a party that requires masks. If one can pass unrecognised, who knows whether anybody is or isn’t on the list?

In life and in the media, there appear to be two separate categories of women. Here, we will call them — for clarity — “Fools” and “Fortunates.” Fortunates make the list, and Fools do not. Fools are the ones who are found, historically, both enacting and suffering violence in the name of beauty, and fail unequivocally at elevating themselves to a state of Fortune. As history is written by the victors, beauty standards are written and undersigned by the Fortunates. Fools go unrecognised and uncategorised, except by the mark of their permanent, personal shame — another injury, in its interior way. Consider this, from an 1889 edition of the Dundee Enquirer: “If your eyes are unattractive, you may make them irresistible by transplanting the hair. Transplanted eyelashes and eyebrows are the latest things in the way of personal adornment. An ordinary fine needle is threaded with a long hair, generally taken from the head of the person to be operated upon. The lower border of the eyelid is then thoroughly cleaned, and in order that the process may be as painless as possible rubbed with a solution of cocaine. The operator then by a few skilful touches runs his needle through the extreme edges of the eyelid between the epidermis and the lower border of the cartilage of the tragus. The needle passes in and out along the edge of the lid leaving its hair thread in loops of carefully graduated length.”

Who would undergo this kind of torture, having been given the chance to avoid it? Simply, a Fool. She is hapless and helpless to stop herself from self-improvement, and so she sews herself into a captive girl from a slasher film. A friend of mine was once strip-searched at a airport after carrying through a number of cosmetics which, when combined, could be used to make an explosive; this is a classic, if somewhat unusual, case of a woman being unFortunate. Fortunate women are never left ruffled by travel, or altered by elements. There is a moment in Nora Ephron’s failed retread of Bewitched, in which Nicole Kidman — who is possessed of the same kind of magic as all other Fortunate women — reveals that she dreams of having “days where my hair is affected by weather.” This may be true of a witch, but a Fortunate woman will rarely, if ever, knowingly diminish her powers, and so the declaration rings false for the audience. If Kidman cannot relinquish control of her face’s micro-movements when smiling or laughing or frowning or crying, why would she ever relinquish control of her hairstyle? Still, a Fortunate woman will often be seen to run as if she’s a movie star dodging the rain, in a gait that’s swift and weightless and bounding and unmistakably careless, even in four-inch heels; careless and not carefree, because here, careless implies that the very need for care or consideration is void. She is not a tripper, nor a stumbler, nor an accident victim, as much as she is peachy and unimpeachable. Hers is a blow-out that weathers the storm, every time. “Control” and “power” are very important words to Fortunate women, being, as they are, super-heroines, witches and goddesses who will smite us occasionally for play or from spite. Have you ever known one of those women whose compliments, you are certain, are secret sabotage? What rottenness, and what better guarantee that you are a Fool, and she is a Fortunate — they are sly, after all, in protecting their assets. But they have been trained to do so by something larger than themselves, and this is rotten, too: the top of the heap has the rarest flowers, but garbage still runs from the pinnacle all the way down.

Here is a symbol: there is a famous photograph of Raquel Welch by Terry O’Neill in which she is being crucified, posing as Christ, and in which her face appears caught between two very disparate moods. At one glance, she is beatific; another, and Welch looks suddenly sad, as if she is thinking of something that’s causing her anguish. Some fortune! Forty-something years later, she would go on to write in her autobiography that she’d been made to feel that her whole existence was in being seen, and never being heard; that, finally, at the age of seventy, she felt able to have conversations with other women — that she felt, eventually, the presence of a sisterhood. Losing her beauty, for Raquel, would become like losing her goddess status: but for now, we look at her picture and only see the golden glory of youth, and see her body with its shallow navel and the tan of her flesh, and picture a martyr’s whip-marks, like sutures, indented all over her skin. What if, instead, there were only one category of women whom we decided

to call, for clarity, “women”? If there were no guest-list, there would be no masks. The need to look like heaven, in this world, can sometimes be hell.

Hotel Tokyo / Yoshiyuki Okuyama / Hadarrah More