Issue 10: Compulsory Party / Passive Aggressive

SLOWING DOWN

BY JAVIER ARROYUELO

The fashion powers, that is the various presidents and chief officers of the huge corporations who determine the course of affairs as well as all those who execute or follow their policies – which includes, regretfully, some sectors of the press- should heed Jean Cocteau’s famous dictum about the need, when acting boldly, of knowing just how far one can go too far. It would be time to put the brakes on. There is too much fashion in the world these days, much too many clothes and bags and belts and jewelry, churned out by a disproportionate number of brands. Moreover, the huge success in the social media of a myriad of sites devoted to all sorts of approaches on the subject heightens the perception of a fashion inflation, or, more disquieting, of a bubble about to blow up. And yet excess seems to be a required feature of fashion’s basic tenets. Luxury, of course, was born to it. It feeds glamour too, which is a prodigal display of extreme artifice. And it could be said that elegance is just an excess of appropriateness.

The fashion system as we knew it up to this day, has French for its mother tongue and its distant but distinct roots int he frivolous excesses of the royal court of Versailles, where the Sun King himself and his consecutive mistresses mastered a careful plan of continual sartorial novelties in order to keep pleasurably tied up the unruly members of the nobility. The stratagem worked and became a tradition and a trademark of French ‘art de vivre’, dutifully carried on by Louis XV and his maîtresses and then by Louis XVI’s consort, Marie Antoinette, the Queen unfairly remembered as just a prodigious fashion freak.

Only briefly interrupted by the Revolution, the monarchy’s show off was perpetuated all throughout the 19th century by the modern bourgeoise, the very people who had abolished and supplanted the aristocracy. The new ruling class set the commercial patterns that fashion has followed to this day.: clothing manufacturing and big department stores, ready-to-wear and posh boutiques, and, then, at the flashy apex of the French Second Empire, the exclusive maisons de haute couture, all of which made fashion grow into a flourishing industry and a broad societal phenomenon.

Still, it is now, for the first time, that the fact of dressing up not only has taken a predominant part in the public and private lives of a majority of people but is also getting to be for many of them the glowing expression of their individuality. I am what I wear. By being seen, I am. Raw silk, dungarees, Uniqlo.

Since fashion is today probably the most conspicous emblem of consumerism, and in practice the ideal medium for unbridled consumption, the changes to effect as a first priority do not concern shapes or lengths or styles but the mechanisms of production imposed by the ideology of profit.

In fact, a alternative way does exist already – and it works. In the past decade it got a name, Slow Fashion, for that ‘s precisely what it is; an unhurried mode of production and consumption, on a human scale, following the principles of sustainability, commited to recycling, reusing, high quality and durability and the fair treatment of workers.

What slow fashion aims at is indeed a new art de vivre that ressembles curiously to the art de vivre that was not only possible but even current before consumerism ruined the game of life. As I see it, it’s all about drinks and meals shared and books read and amovies seen and songs sang and trips taken and nice frocks worn all along and for a long time – that is to say, the little things, the small pleasures, the intimate emotions that we remember fondly and anticipate with joy and that prompts us to count our blessings.

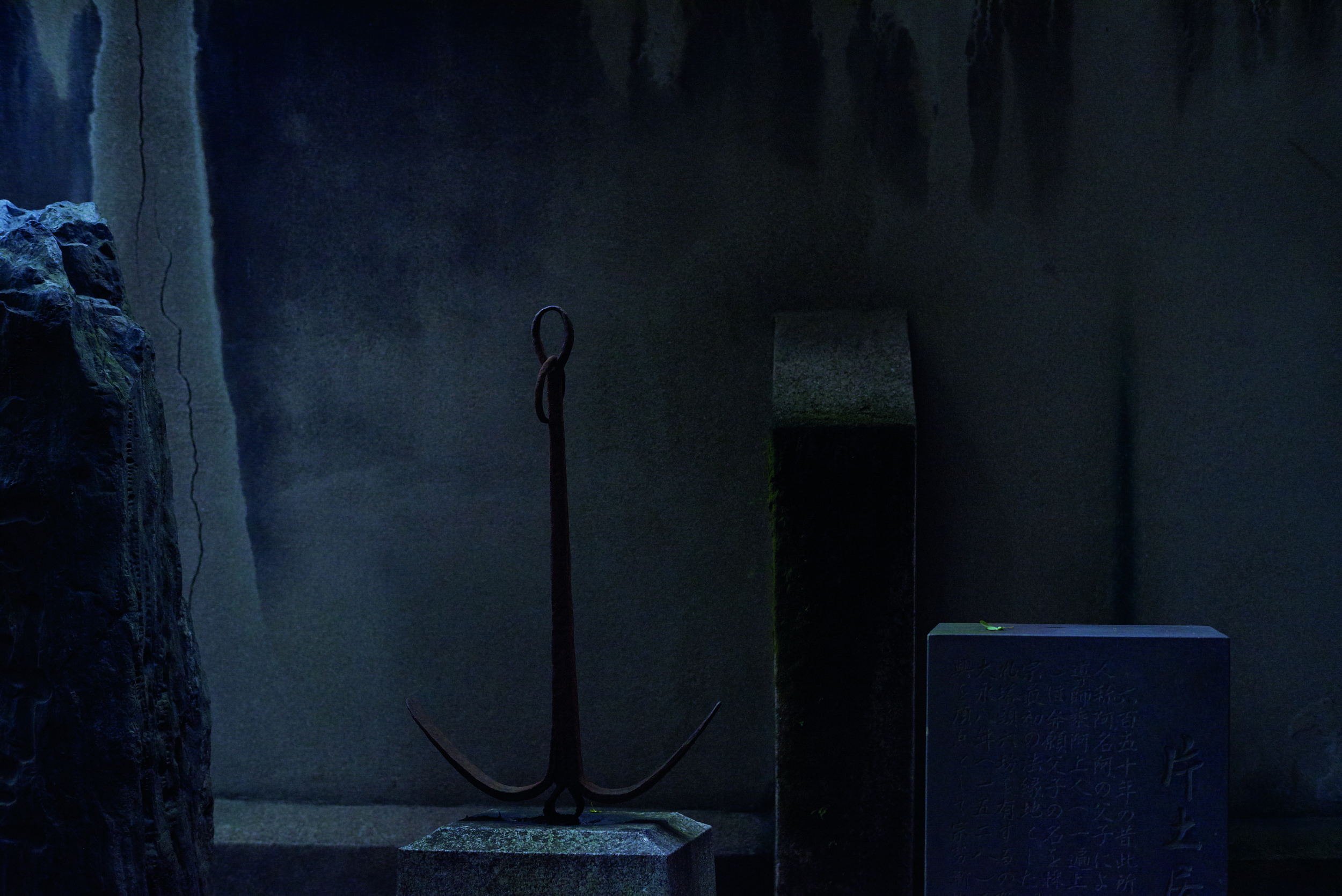

Hotel Tokyo / Yoshiyuki Okuyama / Hadarrah More